Get your pay; get your shots. The first day of each month an officer was designated Pay Officer and handed a briefcase filled with cash and our pay records. But before you were allowed to dip your hand into the pot of gold, a medic administered any shots your records indicated were due. It seems simple enough, a logical and efficient combination of activities, but finance and health care in Viet Nam and at a firebase were anything but simple.

It could get so bizarre that here I am only taking on finances; health care is worthy of its own story. Basically, your military ID and shot record were like a driver’s license and proof of insurance card when stopped for traffic violations; you better have them when requested by authority. The pot of gold – or Monopoly money as we called it – was not accessible to you without them.

- Military Payment Certificates MPC

- My shot record

The Army encouraged having most or all of our salary sent directly to the United States and would then pay us the balance in what they called cash – a.k.a. military payment certificates (MPC). Strongly encouraged, and with a difficult option out, it was akin to being volunteered when you haven’t offered. We called it Monopoly money because that’s what it looked like: small, multicolored papers with different worth designations. It rapidly replaced the piaster as the local Vietnamese currency, and roadside vendors only accepted this military script as payment from Americans. The Vietnamese would laugh if we tried to pay them with their country’s money and offered to sell us all we wanted, as long as we paid in MPC. They would use MPCs among themselves as a local currency, as it was backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. Military. Truth is that it was more stable and worth more to them than piasters.

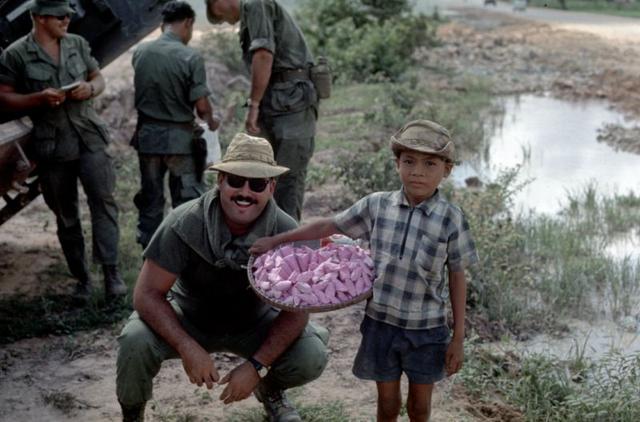

We purchased cold soda, cigarettes and other small goods from roadside vendors or sellers occupying a location just outside the FSB. The Vietnamese were not allowed in a firebase, and we were not to interact with the Vietnamese outside of the firebase. It was too dangerous, as friend from enemy was not a call easily made, but the Mama Sans set up shop anyway and we bought from them.

In base camps, large supply depots and Vietnamese cities like Saigon, there existed a fluid and somewhat complicated money system that made our FSB economy look like child’s play. It’s worth including in the story because it illustrates both a connection and a disparity between the rich Americans and the Vietnamese poor.

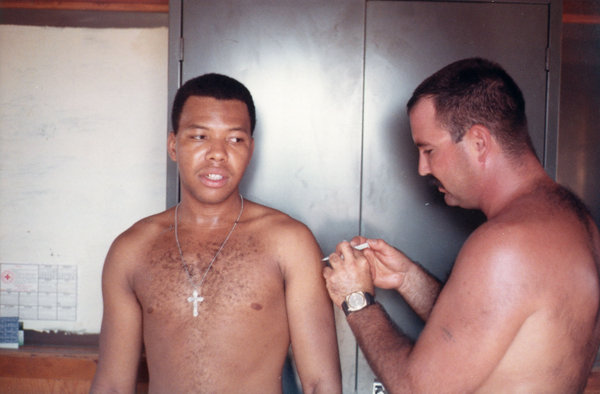

- Pay, pills and shots My photo

- Doc Randy Barnes giving shot. His photo

The Army would foil the Vietnamese from completely making MPC the currency of the local economy by changing the Series. This prevented the Vietnamese from stockpiling it or having too much infiltrate the local economy and drive up prices, increasing inflation. A currency exchange date of old MPC for a new Series would be set. As the old ones would soon be worthless, the Vietnamese, who somehow always knew the date of the exchange before we did, would give their soon-to-be-worthless MPC to an American they trusted, hoping this soul would bring new bills in exchange. The Vietnamese expected that this transaction would not work completely in their favor because there would be a charge for the exchange. But when something will soon be worth nothing, anything is better.

There were other exchange activities that took currency profiteering to a higher level. The exchange of American money, greenbacks, was even more valuable to the Vietnamese. At my first stop in Cam Ranh Bay, the military exchanged our American money for MPC, so the only source of greenbacks was family and friends sending it. I could take an American dollar and exchange it for multiples of MPC dollars because the Vietnamese wanted it so badly.

Know that there were few, if any, Vietnamese men around, as every healthy adult male between 16 and 60 was conscripted into the Vietnamese military, leaving the women, children, the crippled and the very old behind. The Mama Sans outside the bases acted as “middlewomen” for the wealthier Vietnamese who wanted to get their assets out of the country and needed American dollars or gold to do it. They were moneychangers! The rate was good for Americans at four to one, and the women and others in the money supply chain profited as well. The military took profiteering seriously. Any kind of exchange, MPC, dollars or money orders was joyfully punishable by the Army, but the trading continued unabated. Black marketeers have always followed armies.

At the low end of the currency debacle was the sand-coated penny collection at the Cam Ranh Bay base. Picture a rectangular grouping of wooden sidewalks elevated from the beach sand and leading to a platform where US money was magically changed into MPC. There was a building abutting this platform with a two-part door. The top section opened for the transaction, and the bottom served as both a counter and barrier. Soldiers on the outside, money handler on the inside, sidewalks and sand – you get the picture.

There was no one-cent MPC, so after making their exchanges, many soldiers would toss their now-useless pennies into the sand as they left, creating a significant amount of coinage each day and guaranteeing that some unlucky soldier would be handed a sieve and ordered to collect them. It turned out to be lucky me, as I did not escape this duty. As soon as I had completed my transaction, I was corralled by a sergeant and told to “start sifting.” Not something I had envisioned as part of my Nam experience.

So, outranked as I was, I started digging and sifting and then took my haul back up to put in the sergeant’s shack behind the counter, only to find it filled with duffle bags of these pennies. The duffle bags were about 3 ½ foot tall and 12-16 inches in diameter. I was looking at a mother lode of profit because career military people had all of their stuff shipped back home for free – even bags of pennies. I have no doubt that was the plan: use soldiers, preferably FNGs, to gather the harvest and let the military pay for its transfer to the states. I was just 10,000 seconds into my 32,000,000-second tour and had already been used in the first scam I saw in Vietnam.

I soon learned that scams were not unusual. Roadside merchants were selling us our own Army-issued products, even the large cans of bug spray we so desperately needed. There were plenty in the military who had their own hustle – simply taking supplies and selling them. Name a product and you could probably buy it from a Vietnamese merchant whose purchase had most likely been from the American supply chain.