Our tank and APC escorted and protected convoy moved briskly west from Tay Ninh toward Cambodia, throwing up a dust cloud as we passed through open rice-paddy country and into an area that had been recently cultivated but abandoned due to the war. The abandoned paddy dykes were visible, but the area was being speedily filled with trees, grasses and underbrush, so returning it to rice cultivation was going to be a big job. Our convoy’s speed slowed in this area, and somewhere we turned north, continuing a little west. In short order, jungle took control of the land, and the road turned into two parallel lanes just wide enough for a big log carrier pulled by two buffalo and barely wide enough for our equipment. Our speed reduced to a crawl, and the jungle grew to 100 feet or more. Under the trees, it was dark on a sunny day.

Every artilleryman was on edge. Our past operations had been in open rice-growing country filled with people, but we had not seen a local for a few miles and could not see very far into the jungle. Damage to the jungle from bombs and artillery was visible, and some thought they could see unexploded bombs. I never did, but I took their word wanting to error on the safe side. Men were so nervous, I do not remember anyone taking pictures; they held their M-16s close. Our path was pinched on both sides, so unhitching our guns and turning them to fire was going to be a significant problem, as there was simply no room.

- Ready to Convoy My photo

- Convoy arrives My photo

Ninety minutes into our trip, the convoy stopped, and we learned that a bridge had been blown ahead. We would need a portable bridge (AVLB) to span the gap. So, we pointed our howitzers 90 degrees to the road, lowered the gun tube to level and loaded anti-personnel shells into the chambers. The rest of us cannon-cockers took our individual weapons and deployed into the edge of the vegetation, which was five foot from the edge of the road and, in this case, also the truck. I could feel tension all around me. I looked at the APC ahead of us, and the men were writing letters, working on their gear, a few were taking naps and most were laughing at us. Damn! Being scared and laughed at is humiliating!

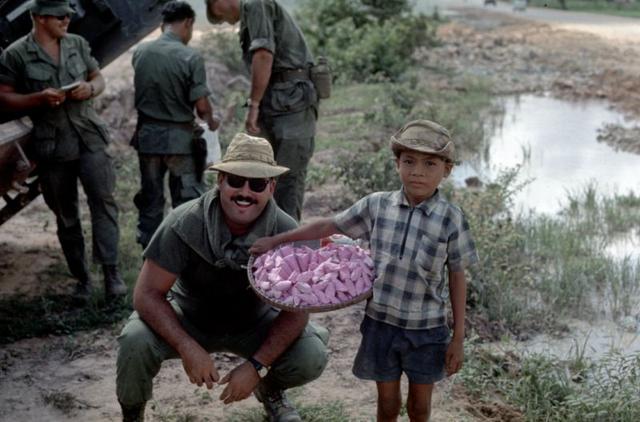

Within 15 minutes, a group of Vietnamese boys, who looked to be about 10 years old, showed up selling cold pop, cold beer and some of the most vile pornographic pictures I had ever seen. Our maps showed no homes near us, electricity was miles away, yet somehow they had cold drinks for sale. The kids showing up put me into hyper-alert because there wasn’t supposed to be anyone around. If these kids knew we were here, I was concerned about who else might know. But none of the troops around me seemed bothered by the boys’ presence as they bought cold sodas. Beer was a serious matter as the 25th Division did not allow alcohol in the field and prosecuted violators vigorously, but I still have no doubt one or more beers were sold. Our Battery Commander, Captain Knox, told First Sgt. Jones to run the young venders off, but this turned out to be one of those no-win situations we often experienced in Vietnam. They were not leaving, and we could not kill them, but we couldn’t take them prisoner either. Our job was strictly artillery, and we were headed to the middle of nowhere. We had to take our chances that the kids were not a set-up for the enemy, which, sadly, could have been the case.

After an hour’s wait, the AVLB pushed around the convoy, taking out some trees to clear a path. It took a half an hour to span the gap, and we then proceeded north to Katum, a Green Beret camp. Jungle scraped both sides of our truck, and the “road” surface was two paths with bumps installed, so our pace was deliberate. If ambushed, we were on our own! I was pumping adrenaline by the pint.

- Portable bridge. AVLB John Clark photo

Clearly, resupply of this camp by road was not a stable, long-term solution, so the airstrip we were headed to repair was a critical cog in the camp’s supply chain. We were part of a force sent to escort and protect the engineers, as they resurfaced and repaired the runway. No one from the camp greeted us, and I never did see a human from the camp. We knew someone was there, as 105 mm artillery was fired day and night, and we heard radio chatter but were never involved in any conversation.

One day, four of our howitzers were towed behind APCs, and we headed west down a dirt path. Part of our FDC loaded the minimum computational equipment needed to operate FDC, including the 3/4-ton truck’s mounts for radios and its battery for power. After a mile or two of travel, we unhitched from the APCs, and our guns sat in a single line shooting over each other because the road was the only dry ground. Swamp and very tall jungle growing in the swamp hugged both sides of the road and made setting out aiming stakes a real chore. Aiming the guns left to right was limited to a narrow tunnel, running west over the dirt trail (road,) so any FDC deflection computation had to send a shell down that tunnel. The reality was that we had to shoot over the gun(s) in front of us, as it was the only route for fire. The concussion that comes out of these guns is strong enough to move your clothing. In this case, the concussion air bombs travelling over us were strong enough to try to pull our clothes forward and ruined our hearing. No sweat GI, this will be an easy day! After all, with a little luck, we would not get attacked from the swamps.

Well, easy with luck and no human error. But, sad to say and hard to admit, we forgot to bring map pins, so the left to right part of our computations would at best be inexact because we had no pins to represent locations on our mapping table. That said, being forced to shoot forward limited potential miscalculations. But fortune shined on us; we found a grunt with safety pins hanging from his pocket and used those instead. It was a timely find, as a call for artillery fire came, and we delivered it to the spot called for. Immediately, someone started screaming over our air communication radio, but none of us could understand him. Turns out it was a Huey Cobra gunship, following the road east that nearly ate some of our 105mm shells flying west. The pilot or pilots were understandably pissed! In our defense, the normal clearances that would have alerted us, as well as the helicopters, was not available. We didn’t even know they were flying along there, had no clue they were using it for orientation.

- Charting table. That is me. My photo

- Ralph Thompson FDC chief My photo

- FDC in the sun. My photo

When the APCs returned, our guns were blocking their passage, and we needed most of their men to help us turn our guns 180 degrees. We also parked the guns to one side to allow the tracked troop carriers so pass. We needed every man to hitch each of our howitzers to an APC, and most of us got wet and muddy in the process. How we turned our 34-ton truck is not worth the space to tell the story, but it was tedious. Our convoy slowly made the trip back to the base, and everyone was tense and watching closely, understanding that the enemy knew we had to return this way. It was the perfect place to ambush us, but we returned without incident.

- C-7 Caribou unloading My photo

- Air strip resurfacing Ny photo

- 105mm Howitzer carried by a Chinook My photo

The nine days protecting Army Engineers while they repaired the Katum airstrip passed slowly, but the nights were full of action. Mortar and small arms fire filled many nighttime hours, but we had no observed targets and only fired at a few flashes that revealed a possible target for artillery. The Vietnamese inside the Green Beret camp shot artillery all night, every night, but having no radio communications, we were in the dark, even literally as it never ceased to amaze me how dark the nights would get. When the airstrip work was completed and a couple of C-7 Caribou landed to test the repairs, someone determined it was time for our group to leave. No argument from anyone.

As we prepared our convoy to depart, many helicopters began landing and belching out South Vietnamese soldiers for an hour or more. Some were carrying chickens, ducks and geese and appeared to have no small arms weapons; most carried M 16s. Their troops assembled slowly and began moving into the jungle in small groups. Forty-five minutes passed with a constant flow of soldiers assembling and following the lead groups into the unknown when small arms fire came from the direction they were moving. As the rate of fire increased, so did my heart rate. Next, the artillery inside Katum started lobbing shells toward the increasing noise of a firefight, and in only a couple of minutes, jet bombers began dropping their loads, shooting rockets and discharging other noisy armaments.

During the heat of this tussle, our convoy started moving south, away from the fighting. All my mental focus was on moving south as rapidly as we could. Ten days and nights of mortars, rockets and small arms fire was enough. Our pace was slow, and every man had all his senses focused on the jungle that closed in from both sides of the road because every inch was a good-to-excellent location for an ambush. Keep traveling south, no stopping. After about five lifetimes, the convoy moved into nearly treeless rice-paddy country, and I dropped out of my trip-sustained hyper-alert mode and back to my normal scared-as-shit one. Welcome home!

Over the decades, I have thought about why we were not sent back to the fighting. Turning the convoy around would have been complex but doable, so maybe it was because we were near the end of our supplies or perhaps we were not needed. During our convoy south, I did not hear radio chatter about fighting on either our air or ground nets and that felt odd. My thought in 2017 is we were not called back because our operational command had no radio communication with theirs. Who knows? A guardian angel?