It was August 1968, and I had been in Viet Nam less than 20 days with no idea how quickly my life was going to change. I was assigned to A Battery, 7/11 Artillery, which was currently located in Dau Tieng base camp, home of the 3rd Brigade 25th Infantry Division.

Base camps provided support to the field units, delivering everything they required to function: food, water, mail, ammunition and an assortment of other supplies. It was typical for a field unit to also be assigned to base camps on a rotating basis. This provided a chance for the soldiers to get some well-deserved rest and refit their gear. Another function was to provide trained backup to the guards in the towers (which were manned by various base camp personnel) in the event of an attack.

Dau Tieng was an FSB disguised and misnamed as a base camp and drew regular mortar fire and rocket attacks, as well as randomly timed ground attacks and nightly sniper fire from inside the base camp. It was an extremely dangerous place, and there I was, an FNG assigned to a place that had been partially overrun two weeks before.

- Destroyed APC John Clark photo

- Damaged APC Randy Barnes photo

Resupply was always risky, and that August and September the enemy was especially active in their attacks proximate to that area. Convoys required significant manpower and equipment, including APCs, dusters, quad fifties, tanks, truck and jeeps. Helicopters also accompanied convoys to provide cover and evacuate any wounded.

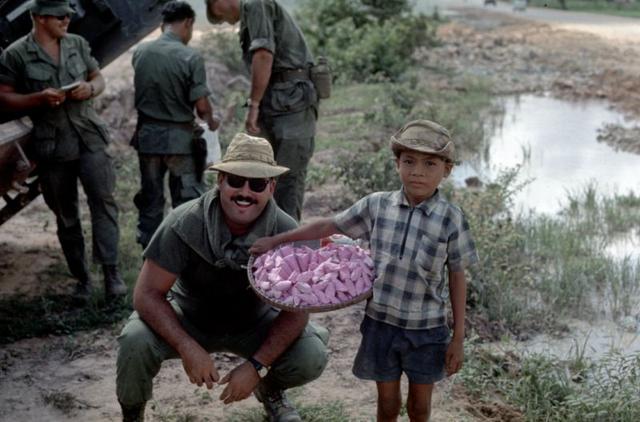

My convoy was taking us from Dau Tieng to Tay Ninh. This was the only road, and it was really nothing more than a dirt path winding through the rice paddies, jungle and a rubber plantations. Pedestrian traffic was always high, and as usual in Vietnam, it was impossible for us to tell friendly from unfriendly. Being the wet season, the roads were ribbons of mud making the trek nearly impossible. There was no other option except supply by air, and the enemy understood this. Enemy Vietnamese would pick spots with the most cover and wait for convoys to roll into their traps.

Ambushes generally began with a startling explosion. A land mine placed under the road surface would take out one of the leading vehicles with the intent of blocking the road and trapping the rest of the convoy. The enemy would then open fire on the convoy with mortars and small arms. The key to surviving an ambush was to escape the killing zone, and this convoy did not have that option. The Vietnamese foot traffic would know in advance the attack was coming and would gather at the outer edges of the kill zone and wait for the ambush to be complete before resuming their trips.

After a three-day delay, the route was declared open, and our convoy headed for Tay Ninh. The route passed through the Michelin rubber plantation, which was thick with trees. To eliminate hiding spots, Army engineers had decapitated the rubber trees on both sides of the road, leaving five-foot stumps for about one hundred feet out from the road on both sides. The tops of the cut trees were removed, bulldozed into piles and burned, leaving this odd area of stake-like stumps.

- Rubber trees cleared away. Randy Barnes photo

- Randy Barnes Safer road.Safer convoys. Randy Barnes photo

We encountered blown-up APCs and trucks, which meant one of two things: it was too dangerous to go back and retrieve what used to be a vehicle or the ambush had happened recently. A mile or two after we emerged from the rubber plantation into the open paddy country, a mine exploded, destroying an APC and blowing a huge crater in the road. All soldiers in the convoy were ordered to seek cover in the water-filled paddies and prepare to be attacked. I was about as green as the rice, less than a month in-country and about to experience my first ambush!

We were stranded, waiting for an AVLB (portable bridge) to span the newly cut and massive hole in the road, so our convoy could proceed. I was totally freaked out! Fortunately, the soldier beside me in the paddy was an infantryman, and I sensed that he knew what he was doing, so I quickly decided to follow his lead. After we settled into the 24-inch deep, repulsively foul water, he yelled to get down. What? That’s it? Get down as low as possible in this water? But what the hell did I know, so I did, even trying to dig myself deeper – ridiculous but true.

We listened intently and heard mortar shells leaving their tubes, which 15 seconds later begin to explode in the area between us and a 200-foot distant tree line. With each round, the mortars landed closer to us as the enemy zeroed in. By the end of the barrage, the mortars were landing very close, and I just knew they were going to hit us, but my new buddy assured me we were safe.

He was right; in two minutes the barrage was over. As my immediate fear subsided, he started to laugh at my previous efforts to dig a foxhole in the water. As I joined his laughter, my tension began to ease. I had secreted away an imperial quart of Chivas Regal I had purchased at the PX but not had a chance to drink because the 25th Division forbade alcohol in the field. Now seemed like the right time to break that rule, and he was eager to participate. Mixing water from his canteen, we polished off half the scotch in the 45 minutes it took for the road to be made passable. When ordered back to our vehicles, I jumped into the front passenger seat of my two and one-half ton truck, and my new friend took his place atop his APC, the vehicle directly behind us. He was facing forward with his legs dangling over the front edge. We were on our way!

- Ambush and stopped convoy. Dave McMahan photo

- AVLB Portable bridge. Dave McMahan photo

A couple of miles down the road, the unthinkable happened – another ambush! Standard procedure called for the convoy to drive straight through the ambush zone, so, having no other options in this second ambush either, that’s exactly what we did. As the convoy entered the kill zone, the convoy escorts peeled off into the ditches and attacked the ambushers who were fighting from cover close by. I was watching all of this going on after my truck entered the kill zone. I heard a noise travelling behind me and began turning around only to see an explosion directly behind my truck, right in front of my new friend’s APC.

As I completed my turn, I saw his legs catapulted into the sky, disintegrating into a stream of blood, bone and liquefied flesh. The next thing I remember was his mangled body lying on the road and his screams for his mother. I was stunned; I had never heard a sound like this come out of a human. His mates, who had also been blown off the top of the APC, immediately grabbed him, tossing him through the rear access door.

Beyond the kill zone, we stopped for a two-seated LOCH command helicopter that was landing. The passenger got out, and my buddy was thrown into his seat on the chopper. The pilot made a beeline to the evacuation hospital in Tay Ninh. The trip must have been a horror for him, as my new friend spurted blood like a fountain and continued screaming. I did not know his name and to this day have no idea of his fate. But he never leaves me; he’s with me every day.

The military had trained me to return fire during an ambush, but I simply couldn’t make sense of what was happening. It was so intense and immediate, I did not fire a single round from my M-16. This FNG in his first firefight did nothing. As our truck headed back to Tay Ninh, I looked at my pants and realized I had urinated and defecated. Seeing that, I proceeded to vomit.

- Convoy Randy Barnes photo

- Convoy 2 Randy Barnes photo

After making it safely to base camp, I completed my paperwork and finished other required duties with battery administration, I got very drunk for the first time in years and sat down on a wooden sidewalk and started to cry, replaying the scene over and over. The sudden attack and his legs flying skyward! His screams! It was the first time in years I had cried and could not stop. I remember being aware of numerous soldiers walking by me, going about their business. One soldier stopped, sat down and put his arm around my shoulder, sitting quietly with me for more than twenty minutes as I continued to cry.

When he stood to walk away, he turned and said, “It’s cool, man – you’ll be OK.” That’s when I finally looked up to see Bob Kelly, a black man. This was the first time in my life any black person had put an arm around my shoulders. It was 1968, and I admit that while I had some prejudice, I had never had a bad experience with blacks. In fact, I had interacted with the few black families that lived in Russell, Kansas where I grew up. I had never been in fights with them or had any other direct conflicts, but I had accepted the stereotypical remarks of some of my fellow “honkeys.”

Many strangers had walked by me, but for whatever reason, a black stranger decided to sit down and put his arm around me. His action and compassion challenged my racial prejudice, which had previously clouded my judgment about the people around me. It made me rethink who I was. I’d just come face-to-face with the very real possibility of death, and if I were to survive Vietnam, I was going to need to judge my fellow soldiers without regard to race and put aside all my preconceptions. More importantly, I needed to set aside my prejudices, so others could count on me to do my best.

Bob and I became friends, but for the next eight months, he would not explain why he had sat down. He was from Harlem, New York, and I was a white kid from small-town western Kansas. Over the next six months, we discussed race, prejudice and our formative years growing up. We even discussed what it would be like if we switched bodies and went to each other’s home, a white man in a black body and environment and a black man in a white body in rural Kansas. It was proof of our trust in each other. Even with the wide range of our conversation, he still never talked about that night despite my repeated requests. Since then, Bob comes to me when I meet a new person and reminds me to be open. I wish he knew how much his act of kindness affected me.

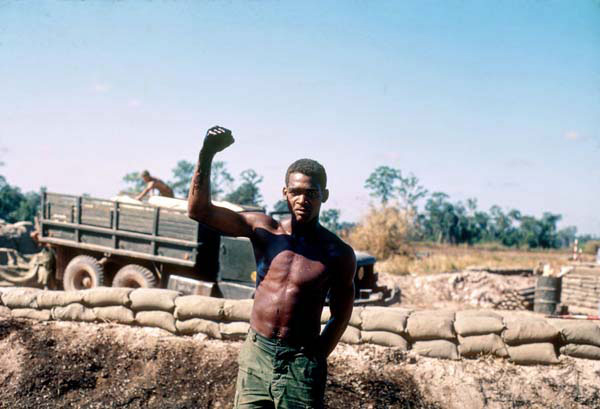

- Bob Kelly My picture