Everything grows in Tay Ninh. The area is a large greenhouse, with near-perfect growing conditions for most plant types. Inside a firebase, weeds were walked on, driven on, doused with various toxic weed killers, cut and burned daily, but still they came.

Growth exploded during the wet season, so rapidly that the weeds could be 3-4 feet tall in seven or eight days, and trees could grow 10 feet in a year. The dry season slowed growth down a little due to the dust-filled air blocking the sun and little water, but still they kept on growing if they were located near an ongoing water supply. Temperature in the dry season averaged 95-108, and while the wet season high was a little lower, it was usually accompanied by 100% humidity. It was always hot, and weeds were always growing.

Most infantry units strung a single strand of barbed wire on small posts in all directions completely around the firebase as part of a last line of defense. The wire was about six inches off the ground and was secured and woven around this forest of short posts, making it almost impossible to take a second step. Minimal weed growth was needed to hide this labyrinth but not much. Nam could grow that in two days, so weeding this area took hours every day. The infantry was responsible for weeding the wire directly outside of the perimeter of our FSB, as well as the rolls of concertina wire that were farther out. Those of us whose jobs kept us inside the firebases weeded the inner perimeter.

The very effective purpose of this wire was to prevent enemy soldiers from crawling close and unseen in the weeds before launching an assault on our firebase. It needed to be done, but the job wasn’t easy. If you happened to trip and fall, you would pay a price for the wire’s protection. You would be entangled in barbed wire and unable to get out without injury and assistance, trapped and painfully pinned down.

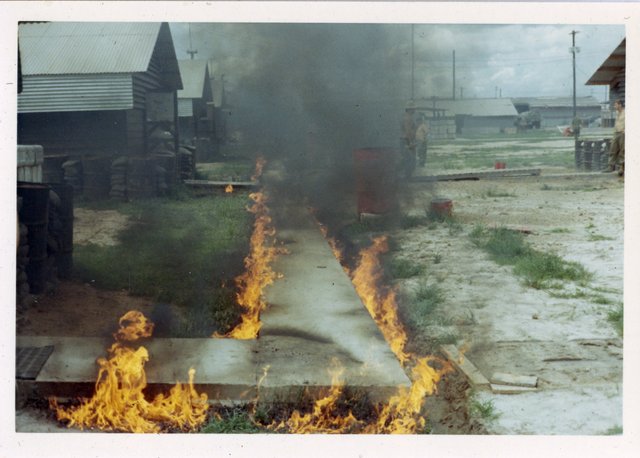

- Fire for weeding. Roger Scatton photo

- Flame thrower for weeding My photo

Keeping our perimeter defenses clear of this almost sci-fi level of weeds required a strong attack, so herbicides were used, along with other forms of destruction. At the same time, Agent Orange, Agent Blue or one of the other “Agent colors,” depending on the witch’s brew of chemicals in the container, were being used to defoliate most jungle and heavily treed areas around us. They contained the much-lamented dioxin that turned out to cause serious health issues, including cancer. Once the trees were stripped of life, bulldozers came in, knocked them down and bulldozed them into piles to burn, which only added to the toxic brew trapped in the dusty air. All of this defoliation and herbicide activity resulted in us regularly breathing this chemically tainted air.

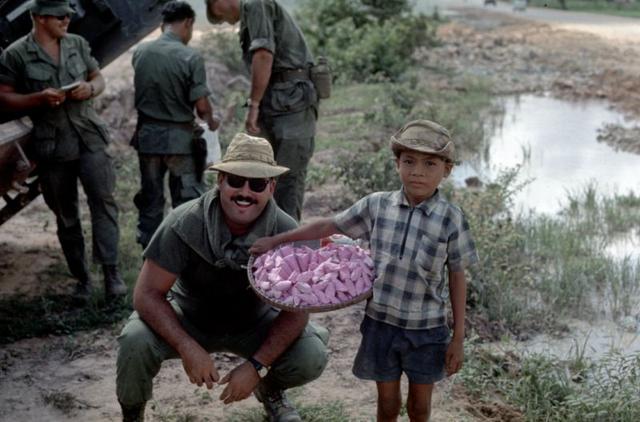

Penta prime was used to keep dust down, but it was only used inside the firebase to keep down the fine dust that resulted from firing artillery. It was only moderately effective because it was a heavy oil sludge, so when you walked on it, the black substance stuck to your boots and everything else it touched. Not only that, each step added either a layer or dust or penta prime. Anything in its radius was fair game to penta prime, as any exposed surface we walked on was contaminated. It was so bad that when the American Red Cross, “Donut Dollies,” and their crew came at Xmas to serenade us, they had to stand in it, and put their equipment and belongings on the ground, which meant on the penta prime. Eventually, their once-clean clothing was inundated with blogs of black substance. In the photographs from their visit, you can see these lovely folks immersed in the grunge of penta prime and dust.

Another dust “note” is that I believe my digestive issue, diarrhea, which I endured every single day of my tour, was due partly to the contaminated dust, along with the interaction and proximity to the herbicides being sprayed. To this day, my gut goes similarly berserk when I smell 24D and that started in Nam over 40 years ago. It was a no-option situation for us. Keeping down weed growth had to be first, so effects of the effort came in second to the point where our health seemed inconsequential.

An additional method of weed control was burning it with a flamethrower but that could only be used by a mechanized unit, as flamethrowers were bulky and heavy to haul around in the blistering heat. In a mobile army, where weight and bulk limit what war tools are available, flamethrowers were not an option for a unit like ours, which had to be air mobile ready all the time.

For weed control at the Tay Ninh base camp, the Army would go to the firebases nearby and levy “volunteers” for a specialized assignment to clean out and repair the perimeter. The guard towers at the base were manned primarily by noncombat soldiers hoping to avoid guard duty again, as they were administrative personnel or transient. The result was often an army of “ones” at the perimeter who experienced very little bonding and, naturally, were more oriented to self-survival. They stayed in the towers, and there were no regularly assigned personnel to do the upkeep and repair of the perimeter. As a result, small and much-needed work accumulated every second, resulting in soft points for the enemy to attack the camp, which they did. These guards were not used to being outside the wire, so it made the best sense to use infantry and artillery personnel from the field to do the job because they knew what to look for and how to make sure the multiple defenses were working and fully integrated.

Weeding our firebase was nothing compared to this work at Tay Ninh, as ours was no more than 600 or 700 feet in circumference. This was not the case around the extensive perimeter of the base camp, where weeding took on a whole new meaning. Frequently, work details were punishment for small transgressions. Since I had a propensity for trouble, I was provided multiple opportunities to partake in the Tay Ninh weeding experience.

It was anything but a “special” assignment. Even the desired time away from my bunker and firebase and having access to the base’s amenities weren’t worth days of chopping weeds. They were long, physically demanding days fighting a never-ending circular morass of weeds. I often wondered if I were there long enough to get back to where I started if it would look exactly the same, untouched and wild. During my tour, I will admit that there were a handful of times where getting back to the firebase was a prayer answered – this was one of them.