Trip to Vietnam

I heard during my tour the difference between a fairy tale and a war story is that one starts with “Once upon a time” and the other with “This is no shit!” I’m not sure these were the exact words, but it hits a central truth, which will be central to you while you read my book. I also believe there are multiple types of war stories. There are ones that are so often chosen for the news, TV shows and movies relating the death, destruction and other true horrors of war. For those who haven’t served in a war zone, those images are what they naturally revert to. But there was another side to serving in a war zone, and it is one that I have been waiting to share for over 45 years.

The stories that follow are not political, argumentative, intended to persuade or to imply my experiences were the same as others. My purpose is to entertain and relate the aspects of my time in Vietnam that I found to be humorous, interesting and/or thought provoking – everything from creating pizza from 1943 C-Rations to the insane weather to a forever disturbing memory of an ambush.

Disclaimer: This first chapter is long and the only one that is chronological. It covers my trip to Nam from leaving the states to arriving at Dau Tieng base camp. As I worked on the heart of the book – various subjects in no particular order – I realized some background on my views and the start of this life experience would be needed to understand “where I was coming from,” which was basically a clueless FNG (fucking new guy) who would rather not have gone in the first place. After this chapter, the rest of the book follows no intentional order. As in says in the “My Vietnam” introduction, these are stories about “Sadness, humor, compassion and frustration — a.k.a. war in Vietnam.”

Ft. Lewis to Cam Ranh Bay

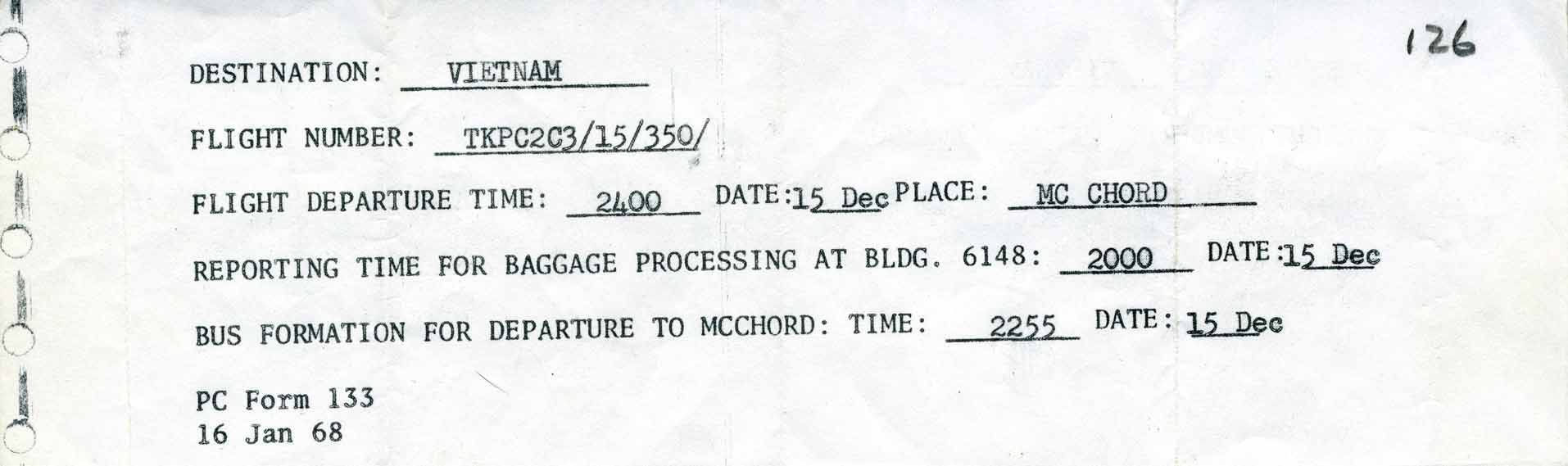

I was among more than 250 soldiers who left Ft. Lewis Washington early one August morning and were bused to McCord Air Force base, where we were loaded on to a Seaboard World Airways Stretch DC-8, headed to Vietnam.

The trip was rocky from the start, as we had to deplane shortly after getting on due to problems with a jet engine. I get it; things like that happen. What I didn’t get was an eight-hour forced rest on the tarmac, in the heat, with no food and no access to bathrooms while the jet engine was exchanged. We had already processed out, so we were no longer allowed in the air-conditioned Air Force terminal we had exited. Not officers, not new guys, no one, as we were no longer in the Air Force system. We were “on our way to Vietnam” even though we hadn’t left. No one was in charge to do anything about it because we were not an organized group, just a load of soldiers of different ranks and purposes headed to Vietnam.

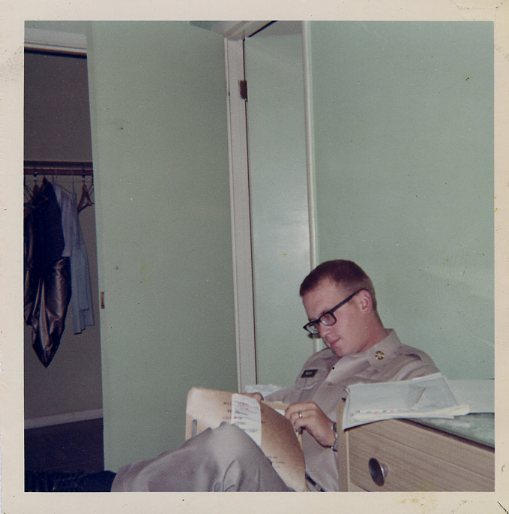

- Ticket to Vietnam Roger Scatton

The plane was packed full of men, equipment and nervous energy as we took off, headed for our first stop in Anchorage, Alaska. We had a short time off the plane to look over the civilian terminal before we loaded up and headed for Yokota, Japan. As our flight settled in, the pilot announced we could come one or two at a time and view the inside of an airliner cockpit and its operations. Cool – that would be interesting! Then he announced that this was their first trip since being forced to land on one of the Kuril Islands by Russian fighter jets due to allegedly violating their airspace. He went on to “comfort” us with the fact that the plane and passengers had been held for only a few days while Russia and the US negotiated a release of passengers and plane and sent it on its way.

Holy crap! The second announcement had been a sobering shock and more nervous energy packed the plane. The mood was somber and quiet because men were looking inside themselves. The idea of ending up in Russia or being shot down for invading their airspace was just another paranoid worry added to the many scary scenarios about what lay ahead for each of us. It made the eight-hour wait on concrete seem like a pleasant dream. I did not hear anyone discussing Vietnam, absolutely no conversation about it. I found this strange but, in hindsight, whether new or returning, each of us was headed to a war zone. Most were going to Nam for the first time, so my guess is that they were wrapped up in fears similar to mine, and the returning men were simply stoic. At this point, the illusion that Vietnam wasn’t going to happen to me was gone, replaced by new and more frightening scenarios. Thus the beginning of “This is no shit!”

Fortunately not detained by Russians or anyone else, we completed the first two stops on the trip. At both Anchorage and Yakota, we were allowed off of the plane, which was a welcome relief since we were packed in so tight. Then, from the Yokota air base, we were headed to Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam. We landed in the dark, and the place was lit like an American city. Why no blackout? This made no sense to me. I eventually learned that this was the most secure base in Vietnam and a main port of entry for arriving men and materials for the war effort. It was guarded by the South Korean Army. Cam Ranh Bay was their assigned territory to defend, and they did it extremely well. They were fierce, tough, organized, disciplined and able to live out of their packs for weeks.

When I arose the next morning, I could see beautiful white sand beaches, a nearby mountain range and a boat motoring in the stunningly deep blue water of the bay, pulling water skiers. Was this a resort or a war zone? Regardless, it sure dropped my tension level. This definitely was not what I expected! Through the mind-numbing, hurry-up-and-wait processing that happens with each change of duty stations, my thoughts were now fully occupied with how to get assigned there. In the meantime, our brand new stateside uniforms, which had been issued at Ft. Lewis before we started the journey, were now exchanged for jungle uniforms. Why not issue those to us to start with? Don’t ask.

Every soldier had a 201 file containing his (no women in combat at this point) complete and detailed history, so the Army did not often let a soldier, touch, smell or basically get near the file because papers could be removed or tampered with. This was the era before computers were used for recordkeeping, so reconstructing a lost or tampered file would be a huge and nearly impossible undertaking. I tell you this because for some reason mine had been given to me, along with a few others, and I had hand-carried it the entire way from Ft. Lewis. I admit I gave serious consideration to dumping it in a trashcan both places where we were off the plane to refuel. After all, I had the only copy of my military paper trail!

It could take weeks, months or possibly forever to figure out how to enter me back into the paper abyss, thereby complicating the paperwork passage into the war zone. Maybe they would think I was sent by Headquarters to spy on them, but the truth is they would probably just think I was a shithead straight out of the brig – and they would be partly right. I didn’t trash my file. Basically I chickened out, but understand what made me consider it. Many of us who had started Officer Candidate School (OSC) had dropped out in order to shorten our tour of duty, so the Army had kindly expedited our trip to Vietnam. For many of us, the decision to drop OCS was a direct result of a new policy of discharging any solider returning to the US with less than 150 days left on their enlistment. Unlike many soldiers who wanted to fight for something, I was trying to shorten my time in the Army and be discharged ASAP.

Cam Ranh Bay to Cu Chi

From the airstrip at Cam Ranh Bay, most of us were loaded into buses and driven to the Replacement Processing Center, where we were directed into a barbed wire wrapped holding pen with the corrugated metal roof on the sand as a floor! I remained in the pen nearly 24 hours (bathroom breaks outside the pen were granted thankfully) until I was called to the administrative building, and the 201 file that had been my ticket into this holding pen was given back to me, along with orders assigning me to the 25th Division.

At this point, I was told to wait in another pen, but this was a four-star pen as we were allowed to leave freely because we had an assigned reporting time for departure and flight. My flight to Cu Chi, home of the 25th Division, was two days out, and I took advantage of the opportunity to eat at an Air Force Mess Hall (better food than an Army mess hall) and walk around the base as an alternative to hanging out in the pen, where lower-ranking soldiers, such as me, were likely to be grabbed by NCOs to fill a work detail.

I was told to check in at the Replacement Administration every eight hours in case my orders were changed, but at all other times, I made it a point to stay away, exploring the massive warehouse that was Cam Ranh Bay. Never in my life had I seen so much stuff in one place. It was mind-boggling, literally acres of anything to support a war that could be stored outside was in the sun in visually numbing quantities, stacks of sandbags, lots full of transportation, artillery and other combat equipment. It was a checkerboard grid the size of a city with roads running at 90 degrees for ease of access. It was impossible to see where it ended, only the bay in the distance.

On my final visit to administration, I was ordered to wait with a group that was assembling in the pen. In not too many hours, we were bused to the base airport and loaded into a C-141 cargo plane headed to Tan Son Nhut AFB, located near Saigon. Hearing anything but engine noise was nearly impossible and after we took off, I was lost in obsessive fears about my future. I did not expect to leave Vietnam alive, and I conjured up some pretty serious and gruesome scenarios about my time there.

Every clerk in my out processing, starting at Ft. Still, had felt the need to explain to me about the night ambushes, guard duty and other horrors of combat, which they had never experienced, even though I was perfectly capable of doing that myself. Later when I met soldiers who had actually been in combat, they compassionately reassured me that I could survive if I listened to experienced members of my unit. What a contrast!

When the plane came to a stop, passengers got off and the C-141 taxied away. We were dropped in an Air Force jet bomber parking lot located on another concrete apron, and each plane had a four-foot tall protective barrier on each side. This parking lot was proximate to runways that launched pairs of jet bombers every couple of minutes, but we could see no administrative buildings containing military people to tell us what was next and that was what we needed. We expected someone would show up with our orders or take us somewhere so they could be issued. No such luck! It was déjà vu – no food, no bathrooms and acres of concrete, but at least there was water available. With no buildings visible and no military vehicles driving by, we were orphaned.

Many hours later, as the sun was setting, a bus picked us up, took us to a C-130 cargo plane that would fly us to Cu Chi but that was all the bus driver knew about our future, and he was the only person on the bus when it arrived. Each of us looked to the others to take a lead in finding out our fate, but there was no one to do that either. The C-130 was smaller than the C-141, louder inside as we bounced around erratically on our 15-minute flight to Cu Chi. I kept a strong grip on the seat frame and anything secure I could get my hands on until we landed. I suppose this flight was progress compared to being abandoned on a tarmac but given my tendency to envision worst-case scenarios, just barely.

Dark had just fallen when jeeps arrived to transport us to 25th Replacement for training, education and more paperwork before being assigned to our particular company or, in my case, battery. Our limos dropped us off at a shabby looking set of buildings where the sergeant in charge showed us our sleeping quarters, as well as the bomb shelter just outside the door of our barrack. He advised us to get very familiar with the path to the shelter from any location and be ready to low-crawl to it if we were mortared or rocketed. This was my first time to hear that advice, and it rattled the hell out of me but forced me into accepting I had found the war – just the edge, a tiny edge.

I dropped my two duffel bags beside by bed. I had been lugging those 50-pounders around since Ft. Lewis, and I was damned glad to get them out of my hands. I had seldom slept since departing McCord AFB but was way too nervous to close my eyes, so I walked outside to look around. Without warning, a massive rocket attack began landing very close, and I flattened out on the ground and began low-crawling madly to the bunker. A passing soldier watched me, had a good laugh, then informed me those were our own 105mm howitzers located next door and not enemy fire landing inside Cu Chi, so it was “Get your ass out of the mud FNG!” It was 2200 hours (10 p.m.) and that artillery fired all night, shots from a single gun at irregular intervals and at times the other five howitzers chiming in, usually firing at a frantic pace. I hit the ground every time they fired! It was the same all four nights I stayed in Cu Chi.

My ear needed to tune into these sounds as friendly, so I could learn not to go for the ground every time. I needed to learn the difference between what I heard and also the feeling of the concussion, as coming from either incoming or outgoing. In the artillery job I was headed to, it was as important as breathing. In fact, knowing the difference could actually could keep us breathing. After midnight, a noise that sounded to me like our artillery shooting was in fact enemy mortars and rockets landing inside Cu Chi and close to us. I fast low-crawled to the bomb shelter and found several men just outside the entrance yelling over each other. I could not make out what they were saying, so I dove for the safety of the shelter to find it was over half filled with water and not tall enough to stand in.

It seemed like this incoming continued sporadically for hours, and our artillery fired outgoing salvos all night. I still could not distinguish the difference in the sounds, but the pressure waves began to feel a little different. Erring on the side of caution, I stayed in the shelter until first light, at which point we were called to formation to attend our classes. My newly issued uniform was soaked, and I was wrinkled like a prune inside of it. The next three nights played out about the same.

We filled out paperwork or waited to do more paperwork and then we were allowed to wait some more. I was sweating a river of water standing in the sun, so most forms I filled out were soaked. I had never experienced humidity this dense, and the temperature felt like 110 when it was a whopping five degrees cooler at 105. In one class, we learned how to clean and shoot a M- 16, Afterwards, we were placed inside an eight-foot deep pit outside the base camp to learn to identify the sounds of small arms fire. Shots were fired from a variety of rifles and machine guns placed at varying and mobile places from our hole, and the instructor identified the weapon and pinpointed the location. Then we were asked to do without assistance. We were being trained to use our ears to identify the shooter’s location and the weapon that was being used without the benefit of sight. It was the most useful training I ever got in the Army because you can see faster and more accurately with your ears than your eyes. To be able to identify the sound of a particular weapon to know if it’s friend of foe within a cacophony of fire was absolutely necessary. I still use this training in my life as another processing tool to know what is going on around me – very useful in the throes of PTSD, but that’s a different story.

Lectures on many subjects such as correctly pronouncing important Vietnamese words, venereal disease prevention or the quality of the leadership, makeup or operating ethics of different units inside the 25th filled many hours of our training days. This training was for new arrivals who sat in bleacher seats, and the instructors stood in a field. Everyone was exposed to the sun and rain that came in numerous, alternating sequences. Sun one minute, clouds and rain the next, then blue sky and humidity – welcome to the wet season. We would see a growing thunderstorm, bend down for a moment and stand up to a multi-hour rain, followed immediately by clear sky, 100 percent humidity and intense sun. Another “Oh shit” realization. Not only was I not in Kansas anymore (not kidding – literally my home state), I was in what felt like another world.

My most lasting memory of one of our instructors was a second lieutenant who had been operating with his infantry company and was recovering in base camp from an AK-47 round that had entered his neck, just missing the main arteries and windpipe in front and missing his spine as it exited. He had been incredibly “lucky” because if it had been an M-16, he would not have made it, as the shot location would have decapitated him. Here he was, despite having nearly died less than three weeks earlier, in a hurry to return to his infantry unit. This had no place in my rational mind. He had barely escaped death and appeared anxious to return to his unit as soon as he received a medical release. To me, he had just won the living lottery, yet he wanted to go back.

It made me even more aware of just what the fuck war meant. Overriding my respect for his dedication and courage were my horrific scenarios of what could happen. Thinking back, after spending four nights with mortar and rockets landing around me in Cu Chi and no one to explain what was happening, I now believe there was an additional reason this lieutenant stayed in my mind. It was the realization that people are trying to kill you and the absolute possibility of death. Perhaps this instructor had no option, but if he did, he sure didn’t exhibit any reluctance to go back – that is real courage.

Cu Chi to Tah Ninh

Once we were trained, we were handed our goodies, put on a C-123 and sent on our way to Tah Ninh. On this flight, I met the guys who wanted to help me adjust to Vietnam, unlike the ones in processing who apparently had been lying like hell about what they had “done” and how awful it would be with the intent of scaring FNGs, effectively adding to and increasing my natural fears. These men I was travelling with were different. They’d been in combat, knew the score and cared enough to help an FNG realize he might make it.

Helicopters came and went often, while fixed-wing aircraft, not so much. I bummed a jeep ride to my unit so was not forced to walk holding those heinously heavy duffel bags in each hand. Roads at Cu Chi and Tay Ninh were dirt surfaced with potholes, had low spots filled with water and were muddy. Arriving at the A Battery 7/11 bureaucratic and supply headquarters, I went into the orderly room and presented my copies of my assignment orders to artillery. It took more than three minutes, but one of the three soldiers finally acknowledged my presence as a soldier, but not as a human being. I was still an Army of one, feeling like I belonged to nothing. In terms of physical environment, each orderly room I passed through during my 19 months in the Army felt much the same, but this one had the advantage of torrid heat and stifling humidity.

David Hockman, who looked like a long haired hippie, was our clerk and the only Harvard graduate I met in Vietnam. He handed me a pile of papers to fill out, took my 201 file and put his head back to his typewriter, the clerk’s instrument of war. Our battery had zero air conditioners when I arrived and the same number when I left, so fans provided the only relief when they stirred the sticky air. I sweat-soaked another pile of paperwork as I filled in forms, most of which I had already filled out at each stop getting there, but paperwork was the Army way to categorize soldiers into multiple “boxes”.

Correction of typing errors was not authorized on Army paperwork so not making mistakes was critical. David could type almost error free, so there went my chance to take his job! After a couple of hours, my papers were in order, so I was sent to supply to be issued an M-16, including ammunition and clips, a steel helmet, flack vest and other military-issued items specific to a 105mm artillery battery soldier.

I was shown a cot in a barrack, the location of bomb shelters, a shower that was out of water and an outhouse that stunk like the one on my grandmother’s farm. Before dark, one of the orderly room soldiers informed me that the firing battery wanted me in the field tomorrow and that we would travel by convoy to Dau Tieng. Convoys were frequently ambushed on the route, and for the next three days the route was closed and the convoy cancelled. This cycle of cancellations was increasing my fear and paranoia. Nightly mortar and rocket attacks, along with American artillery guns shooting from inside the base camp kept me on the ground low-crawling to a bunker due to my inability to distinguish friendly from unfriendly artillery fire. This was how I spent most of my time in Tay Ninh, except when I was in a shelter. At least this one was dry inside.

On the fourth day, the convoy set sail on our road journey, a regularly spaced line of jeeps, trucks, tanks and APC’s making their way on a mostly muddy dirt road that ran through rice paddy country. I was in the cargo part of a three-quarter ton truck that was tarp covered except for a “Conestoga wagon” opening at the back, showing where we had been but not where we were headed. I was alone and seated on a pile of clean laundry bags, with a choking cloud of road dust entering the opening, as we drove on dry sections of road. Everything was unfamiliar, and I had no one to ask questions about what I was seeing. My fear and paranoia were running wild, and there was nothing familiar outside the truck that I could use to ground my thoughts. The last part of the trip was through a rubber plantation and alongside the road were some destroyed Armored Personnel Carriers and a tank. Holy shit! Based on my experience so far, things were looking progressively worse.

Fortunately we arrived at Dau Tieng base camp with no incidents. Along with clean laundry and mail, I was delivered into the care of Captain Knox, First Sergeant Jones and my immediate boss, Ralph Thompson. Thus began the serious part of my Vietnam vacation.

Note: From here on out, the chapters are written by subject, as indicated in their titles, so feel free to jump around if you like. Nothing like an interactive website…