Deadly diseases were common in Vietnam, and malaria was rampant. Any mosquito could be a carrier, and we had an excess of them. One fine day we were dropped and driven into a swamp for three days to construct a third FSB Schofield – I had no idea what had happened to the first two. The mosquitoes were as thick as a Vietnamese rain.

Constructing the fire base was nearly impossible, just filling sandbags with that mud was a nightmare. After two nights with no sleep, I shoveled a ramp from mud to make a sleeping spot that kept the head end of me out of the water. I fell asleep on the ramp without a shirt, and when I awoke, the front of my torso was nearly solid red. My first thought was that I must have been injured during the night, so on went my glasses for a better look and, lo and behold, that solid red was built from hundreds of tiny blood trails from mosquito bites.

At mid morning, we were alerted that we would return to Dau Tieng in the afternoon, and we could not have had better news. When we had first arrived at the swamp, John Clark was ordered to drive one of our duce-and-a half trucks into it. He reminded the Chief who gave the order that the truck was “gonna get stuck,” but was ordered to do it anyway. He nearly buried it in the mud. None of our equipment had the power needed to pull it out. In addition, one of our howitzers had dug its trails into the bottomless mud as we shot the gun, and it was not leaving. Our solution to both problems was to call for a “Super Hook,” the most powerful helicopter in the Army, to pull them loose. Both the gun and the truck resisted its pull, and the chopper used full throttle before a loud sucking sound told us the truck had been released and set on the ground. Then the gun was attached to the chopper, and another POW was freed from the mud prison.

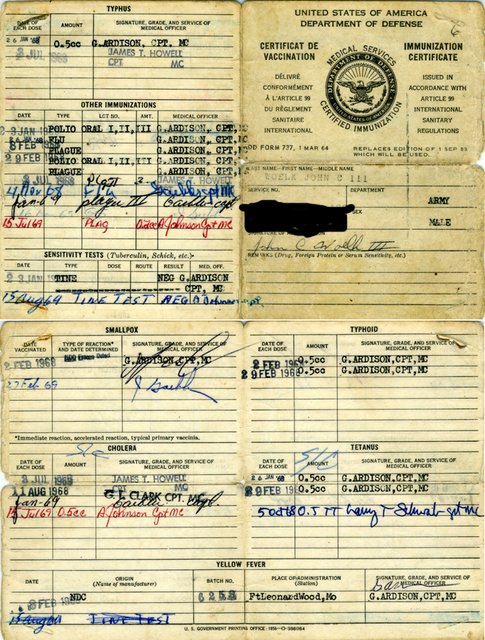

- Checking our shot and pill records My photo

- My Army shot record. My photo

In the meantime, my bites began itching as soon as I was aware of my plight, and no medicine was available to staunch the irritation. I did wear a shirt that day to limit the mosquito attacks, and it felt like sandpaper rubbing my skin as I moved underneath it. Not scratching the bites was a correct strategy, but I could not stop. My FDC mates were yucking it up about my scratching and pimping me about sleeping with no shirt, but at the same time wanting to know why did I not suggest building their own sleeping ramps so they could also have stayed partly dry. I had no decent response, guilty as charged. If malaria was coming my way in Vietnam, this was a hell of way for it to happen. It was also a great lesson to become a regular at taking the Army-mandated pills on schedule, and I complied fully. After a week of maddening bites, I celebrated when the small residual lumps went down.

Upon arriving in Vietnam, I was given a large orange pill to swallow and told that I was to take one of them weekly. It took only three hours for me to have the “runs” that persisted well into the next day, and I got the same problem each Monday thereafter. Acloriquine-primaquine-phosphate tablets caused other intestinal ailments also, and many men decided to forgo taking them. As we left Vietnam, we were given six pills to take for six weeks, and I did that. I have wondered since if the pills worked as promised, but I doubt statistics were kept or could have been.

The exact date escapes me, but we were now issued a small white pill to take the other six days in a week. Dapsone (diaminodiphenyl sulfone) was not well received, so the medic was ordered to be sure we were taking them. His assigned task was to observe each of us taking our pill, and check off our name on a daily record sheet. Doc was not well received on his mission and resorted to marking the list without watching anyone except the officers and NCO’s. Dapsone kept the runs running full bore the other six days. Because of my swamp experience, I took them, with regret, on every trip to the crapper.

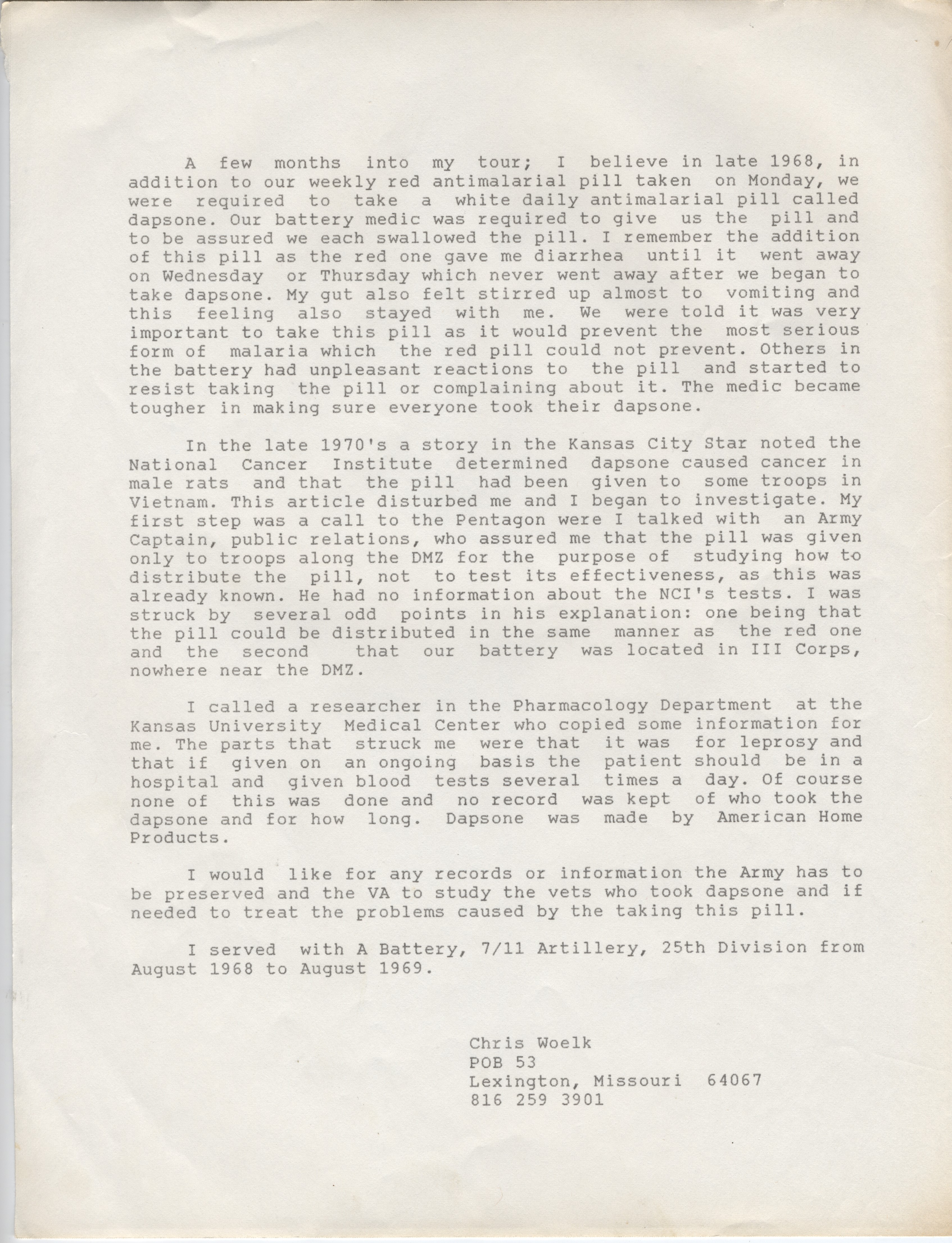

- Dapsone My letter