Zero.

It’s not often in life that having nothing is a desire, much less an outright obsession. But in Vietnam, it was the most sought-after goal of every soldier, the beacon of light at the end of a harrowing journey. It was the hint of survival, as the days of duty counted down from “too-many-to-think-about” to the numbers that reminded you that there was another reality back in the world beyond the jungles and rubber plantations. Numbers that dwindled down until the day you had feared would never come appears; your number hits zero, and you hop aboard the freedom bird to wing your way toward family and friends, toward a place where you can once again breathe freely.

Most men used a matrix of cells that represented the days they needed to survive, somewhere around 365. A cell would be blacked out when a day was served, and the remaining open cells were a graphic representation of the days ahead. The matrix looked like a tic-tac-toe board on steroids.

The first 30 days, I did not start one, but when I did decide to start, true to my nature I went full force. I created 12 of them, so I could mark off a day as served every two hours.

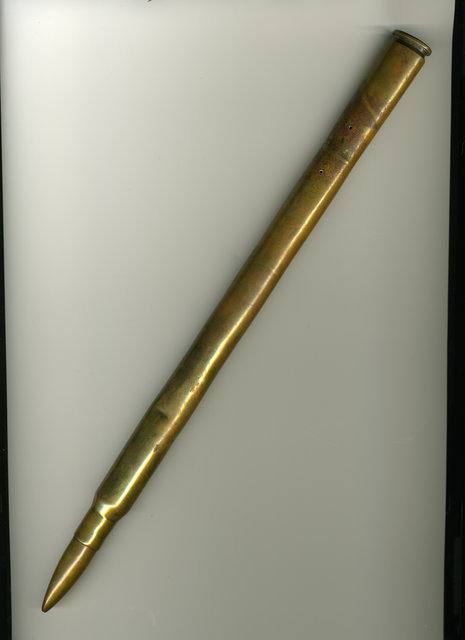

The countdown to the end of a tour was very important. Some even had the fact that they were short written on a helmet cover. Even those who were what we called “gung ho” about the war, career soldiers or working towards transfer to a different job in another tour knew and counted down the days of their tour. The army hated the idea that we would be doing this, as it didn’t exactly reflect well, but they couldn’t stop it, as it was rampant. Some even carried a short-timer’s “stick,” and, to be honest, there was a respect for these men having made it that far. Ultimately, in some way, it was everyone’s goal. Even the high-ranking officers knew a short-timer was different, might go off on them or a myriad of other actions related to the stress of just making it through those last days. When the end is near, it changes you from the inside, and it was a common experience.

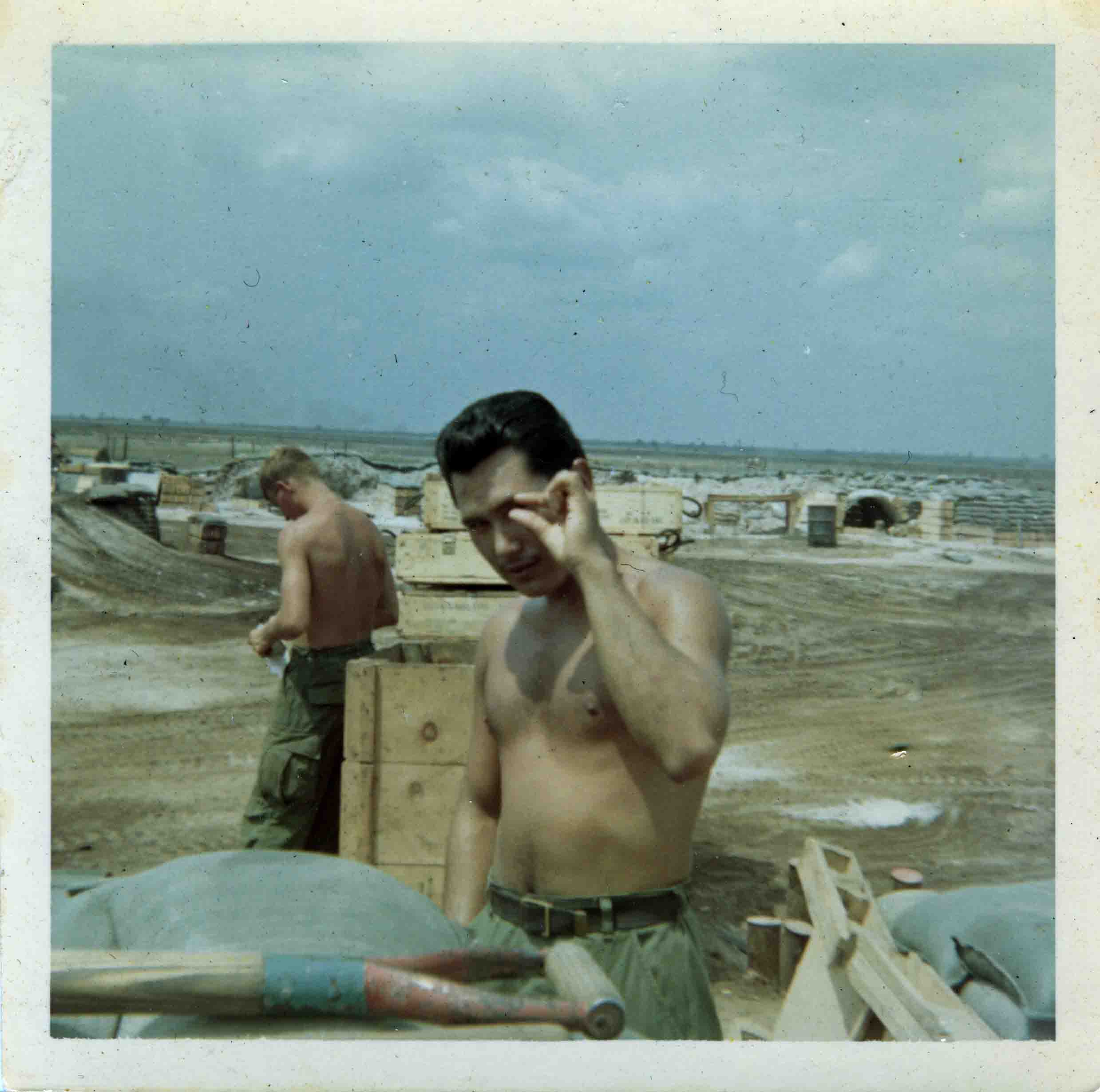

- Roger Scatton Photo

- So Short Wil Fryer photo

They also couldn’t stop the peace signs many of us displayed, often with our dog tags. There were many, like me, who went to Vietnam undecided about the war, having been drafted or having enlisted in order to “have a choice.” But then our experiences and the realities of the war and its attached politics could turn us against it. Countdown for us was home and done, not another tour. Some were against the war based on what, to us, was the futility of it all.

At least in my experience, and I imagine that of others serving in combat, how we felt about the war was pretty much irrelevant in the day to day. It was all about survival and taking care of each other. You can’t be undependable in a combat unit. While there may have been an occasional discussion, opinions about the war were pretty much left to a peace sign. Also, in my opinion, there was no room or desire for heated debates, taking sides or holding grudges regarding the war. Like race, religion and other differences, in a combat unit any possible issue with diversity was overridden. We were isolated; you did your job and did it as well as possible – period. That feeling often waned when short.

Being short resulted in a way of thinking that was counterintuitive, causing us to give those who were short a wide berth. It’s understandable that being short would cause most to become more cautious, as freedom was so close there was more reason to be extra careful so you made it out. But that is doing the opposite of what is most effective in preventing problems inside a combat unit. We didn’t know when or how our base or the units we were covering would be attacked. For us, as for any combat unit, it was act first, think later. Sometimes we had an idea where the enemy was, but it was nearly impossible, as they were mostly hidden. There’s no time to think. When it happens, the wise man’s path to survival is immediate reaction. Think first, act second is the way most of us are raised, and rightly so, as it is useful to think first – just not in combat.

To a certain extent, when you only have days to serve in what is a transient situation, you can become an army of one – less incentive or motivation to be part of a group. This is flat-out more dangerous. A short-time cautionary action could be not walking point or being passive about it. In a firebase, it was not taking an assignment as a forward observer humping out with infantry or an engineer not working booby traps or other dangerous jobs. It could be an officer in a field job going to the rear. Short-time thinking includes a loss of concentration that is paired with being less aggressive, so those on that mental track made these decisions or someone made them for them.

Given the understanding of the mind shift that inevitably happened, as well as the potential increase in danger that the short person could bring, fellow soldiers gave short-timers a wider berth. Again, this was out of respect for making it that far, but it was also for the good of the unit. Even behaviors that would not normally be tolerated were accepted by almost everyone when someone was short. This status is understood, and those who were short were not given the dirty work details, were put on lighter duty, sent back to base camp etc. It was the best route for everyone involved. To me, it was why not? When you’ve gotten short, you’ve earned reprieve.

For me, and for many others, I believed I would die in Vietnam. But when I became short, I began to think I might make it home alive and in one piece. In fact, it was a very sudden realization despite my 12 calendars. It’s one thing to know short is coming; it’s another to feel it. My short story is that there was a song by Jose Feliciano that was the last song I heard leaving the states: Come on Baby, Light My Fire. I was listening to the radio at the firebase, short but not really believing it, when I heard that song again. Bam! It hit me upside the head that that I could be going home and soon! I could survive and my numbers would dwindle from 30 days to 15, then 10, then seven, then the states. Zero was no longer just desired; it was possible!

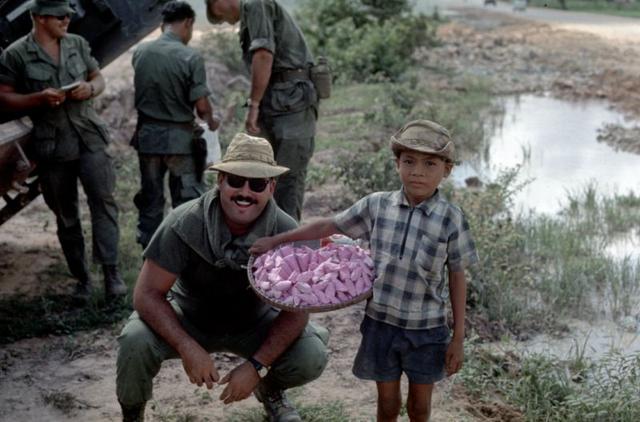

- Chris Woelk photo

- Chris Woelk photo

When I accepted that I was short, I engaged in some of the more minor “normal” activities, but I also deliberately put myself in more danger. This is not something I’m proud of, just something I did and, at the time, was not sure why. I just knew from what I’d seen that my behavior was not normal.

I put myself in more danger when short, instead of hanging back. Crazy, right? I can tell you that, in hindsight, I know it was, but that’s what I did. To this end, I volunteered for a firefly mission, where you put a spotlight and a mini-gun inside a Huey helicopter that is open on both sides, find enemy combatants in the dark and take them out. It does, however, also let them know where you are; you become a target so you better be right and you better be first. I think I did this to prevent myself from falling into the think first, act later mentality. I did not want to find myself using caution where action was the right move, so – in a final hindsight – it might have been smart, but, really, there is no way to know. It just was what it was.

On the “normal” reaction side, I spent hours and hours devouring a book on restaurants in the San Francisco Bay area – pun intended. A friend, Thelma Clark, had sent me The San Francisco Underground Gourmet: An Irreverent Guide to Dining in the Bay Area: Dinners from $2 by R.B. Read. I memorized the damn thing to keep me focused on the fact that I might have a life outside of Vietnam.

Know that I saw few heavy American soldiers and no overweight Vietnamese during my tour. Vietnam was a sauna, and, like others, I had lost significant weight, 65 pounds to be exact. Most of us lost so much weight that custom-made suits from a Hong Kong or Korean tailor operating at Tay Ninh for – get this – $20 or $30 dollars were made larger, knowing we would gain the weight back upon our return to the world. I had bought four of these and within a few weeks of being home, none fit. No more reading about real food, no more C-rations. I was all in, and it was wonderful, unused suits included. Eternally grateful to have made it and full of epicurean and other “first-world” wonders, it was a great and smooth reentry. Being short had helped prepare me for my return home.