My first impression of Vietnam was an unusual and pungent smell, along with humidity unlike any in my past life, and I was not even off the plane! The aroma hit me like a knife up my nostrils; my first thought was animal waste including human, mixed with rotting plant material. That turned out to be a good guess. I could feel the weight of the air; the aroma was so intrusive.

During the 10 to 12 days it took to reach the field component of A battery after I landed at Cam Ranh Bay, I had almost no contact with any Vietnamese person. I did see a few up close and many at a distance. The adults seemed to be about the height of a freshman in my Russell, Kansas high school and slender. Not a single fat person. Some of them looked young, but I was unsure as their age and size did not match as I expected. The two didn’t correlate accurately compared to my experience with Americans.

After my first interaction with the Vietnamese, I was confused. Confused about how I was going to win the hearts and minds of these people, confused about my future and confused about my place in the upside-down world that I now lived in.

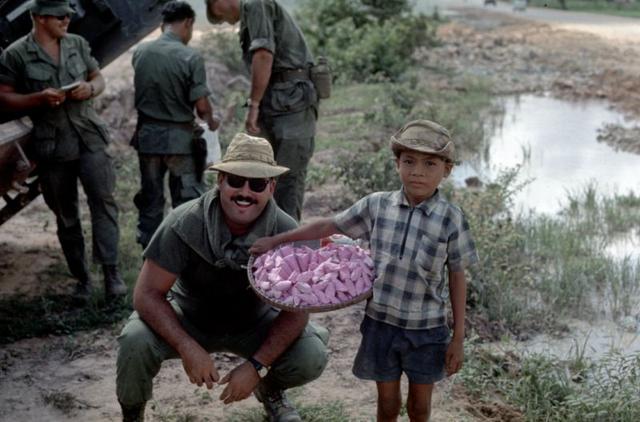

- Pepper vendors. Randy Barnes photo

- Business lunch Randy Barnes photo

Traveling on a convoy with me were some older Vietnamese women who communicated by stating what appeared to be a noun, followed by a rating system that used numbers from 1 to 10, such as GI #1 or GI #10. It was difficult to understand the words they used, and I had to ask for repeats on everything, but since I understood not a single Vietnamese word, it would have to do. My grandmother had friends who were recent immigrants to America that spoke several European languages, and if I listened closely, I soon understood what they were talking about. I expected to do the same with the Vietnamese, but it never happened. I had limited interactions with them, and perhaps with more time, I might have caught on, but I doubt it. It was decades later that I learned the meaning of their words depended on tonality. While I was there, I was definitely not listening for tone imparting meaning. So much for meaningful talk with the locals. Using a 1-10 numeric rating system, language was at #10 because what could be communicated was severely limited. However, it was better than nothing.

Rural roads were filled with people in every spot the convoy passed. Even after our convoy was ambushed, groups of Vietnamese gathered at both ends of the “kill zone” waiting anxiously in a human traffic jam until it was safe for them to pass and continue their journey. Our combat did not delay them for long. I started observing and remembering small details about each person but how to tell friend from enemy did not pop into my head, and, frankly, I never did learn to differentiate them by looking – unless they were shooting at me. Foot traffic along the rural roads we traveled was heavy during daylight. At early and late light, the traffic was like urban, rush-hour traffic, as people moved from home to the rice fields and back. Women and young boys were a large percentage of the traffic, and the boys were often driving oxen. Most of the time our traveling among them felt relatively safe. The young boys herded the oxen easily, but if an American got close, the animals got agitated and could attack. The few adult Vietnamese men in the crowd moved slowly because they were old or crippled; otherwise, a trip to the Army or prison was in their near future.

- Saigon street 2/1969 My photo

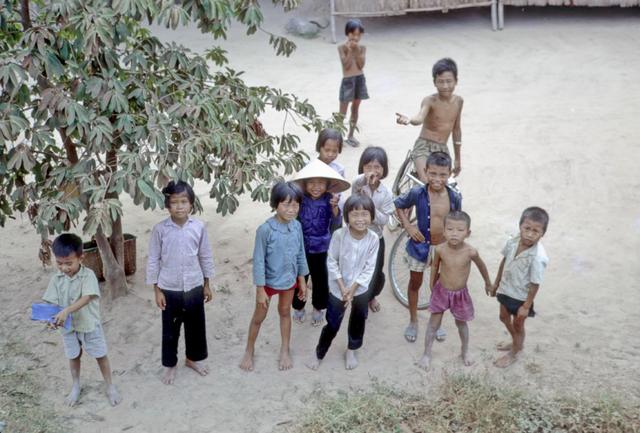

- Rural kids begging. Randy Barnes photo

Over the next 10 months, my dealings with the Vietnamese were limited to buying something from a roadside merchant, talking to the several women who swept floors and did other household chores at the administrative part of the battery in Tay Ninh and a few interludes with boom-boom girls (prostitutes). I was not learning much about the local culture. My attitude about Vietnamese people began to match that of other men in our battery. I suspected every Vietnamese of being an enemy and tried to deal with and watch them as such, at all times. This was the case even in base camp where all locally employed Vietnamese were alleged to have been “checked out” and wore an identity card hanging from a string around their neck. Anger began increasing in me and was fueled at every contact with Vietnamese, even driving by them made me angry. Suspecting and closely watching every Vietnamese was not an attitude helping us win hearts and minds, but it was hard to do otherwise because of the potential cost. After seeing one “seeming” civilian shoot a GI, I had to generalize suspicion to every Vietnamese. All negative interactions with Vietnamese increased the scope of suspicion and time in-country hardened our attitudes.

In February 1969, I traveled to Saigon to take a college graduate school admission test. My M-16 was confiscated and held by Military Police until my trip home, and this would be my first contact without it when dealing with a local Vietnamese. Everyone around me in this crowded city was a local! I calmed myself and got some help finding The Vietnamese/American Association at 55 Mac Dinh Chi. An MP at the front gate of Tan Son Nhut Air Base called over a Vietnamese man peddling a bicycle with a seat mounted over the front tire. The MP instructed the driver where to take me and the amount to charge. The driver delivered me safely, and I felt like a lord, riding in style on the way to the hotel. That driver made sure that he became my tour director of Saigon. Every day after my tests were over, he was waiting outside, ready for whatever I wanted. I was staying in a multistory, luxury hotel in downtown Saigon, paying peanuts for a room. The hotel had a unique service; young women would visit my room with offers to help me make it through the night for a fee and some did.

- Rural Tay Ninh road. My photo

- Country road Tay Ninh My photo

Literally any time I opened the hotel door, the driver was there and ready to go. There were many seated bicycle “taxis” competing for clients, and he made sure none of the others got near me; he was protecting his golden goose. He took me on several long tours, stopping so I could take pictures when I wanted. I admit I was nervous that a Vietnamese male could take me wherever he wanted, and I did not have my M-16 or any weapon to stop an assault. When he refused my request to drive into a crowded slum where shacks were stacked on top of each other, lining both sides of an urban river, worries about my safety with him eased. I even began to “get his meaning” when he gestured or spoke, even though I only understood a few Vietnamese words. After five days I liked the guy. I trusted him!

Our battery operated only with American military units and never worked a combined operation with the Vietnamese, so we did not learn much about their soldiers. In 1969, some infantry companies went on combined operations, and the stories they told were mostly negative. Some infantry units used Vietnamese who had “switched sides,” called Chu Hois, as scouts for spotting booby traps and ambushes on combat operations. Everyone knew they were an enemy, so one or more American infantrymen were assigned to watch them 24/7 and make sure they did not get a weapon. Any time one was in our FSB, I slept very lightly.

During my last 60 days in Vietnam, I spent more and more time in base camp and tried to learn from the Mama Sans about their lives, but language was still a massive barrier. I showed them pictures in American magazines such as Time, Life and Playboy, and their reactions were disbelief, amazement and laughter. The large tits on the Playboy women were the most amazing things of all to them (to me as well). In late July 1969, Americans landed on the moon, and no matter how I told them about it, they laughed and implied I was full of wild tales. Details about America were beyond their understanding, especially technology (Today I understand how they felt.) and sounded like a fantasy.

Much of my work during those last days was acquiring and delivering supplies at whatever FSB we occupied. The preferred way was by truck delivery unless a helicopter was available. A Battery possessed trucks to pull the water trailer for ground delivery, and we could schedule those times. Helicopter units were in charge of their own schedule.

- Base camp worker My photo

- Local workers lined up to enter base camp My photo

- Making do. Roger Scatton photo

- Roger and Vietnamese workers Roger Scatton photo

During my free time in base camp, someone, I think Dick Waddell, introduced me to several Vietnamese who interpreted for American and Vietnamese military units. Two of them I can picture and remember. One was Sgt. Kai, and the other called himself the Vietnamese Wilt Chamberlin because he was taller than most Vietnamese males. Offer a cigarette and they took it even if they did not smoke, letting it burn away. I felt used by them wasting my offered cancer stick, even though 200 cigarettes only cost me $1.15 at the PX and were often available free if I looked. It wasn’t until later that I found out they were taking them to be polite.

One of them kept my home mailing address and began sending me letters in late 1971, asking if I could help him get to the US. I responded to each letter, but as his letters continued into 1973, he never mentioned getting one from me. His letters became panicked, pleading for me to help get him and his family to America, but I had no power to do anything even if he had received my letters. His letters stopped in 1973, and I wish I could have helped him. I had deep concerns about his and most rural people’s ability to adapt to a life in America, but I understood his cries and desire to have a shot at living in the “world.”

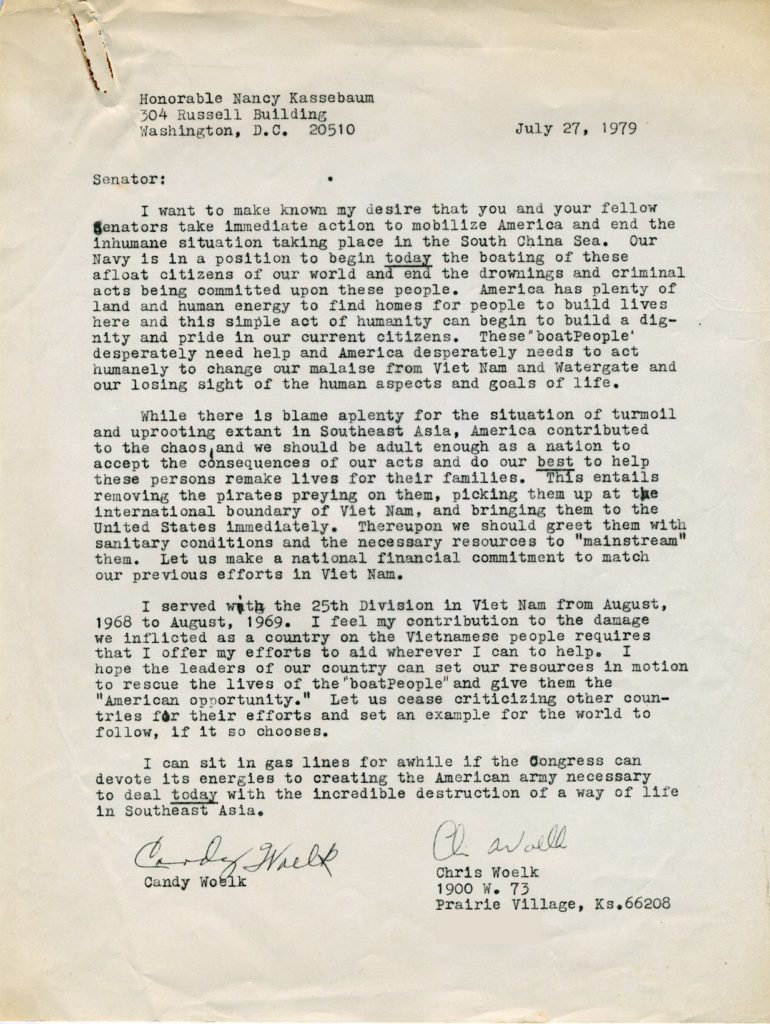

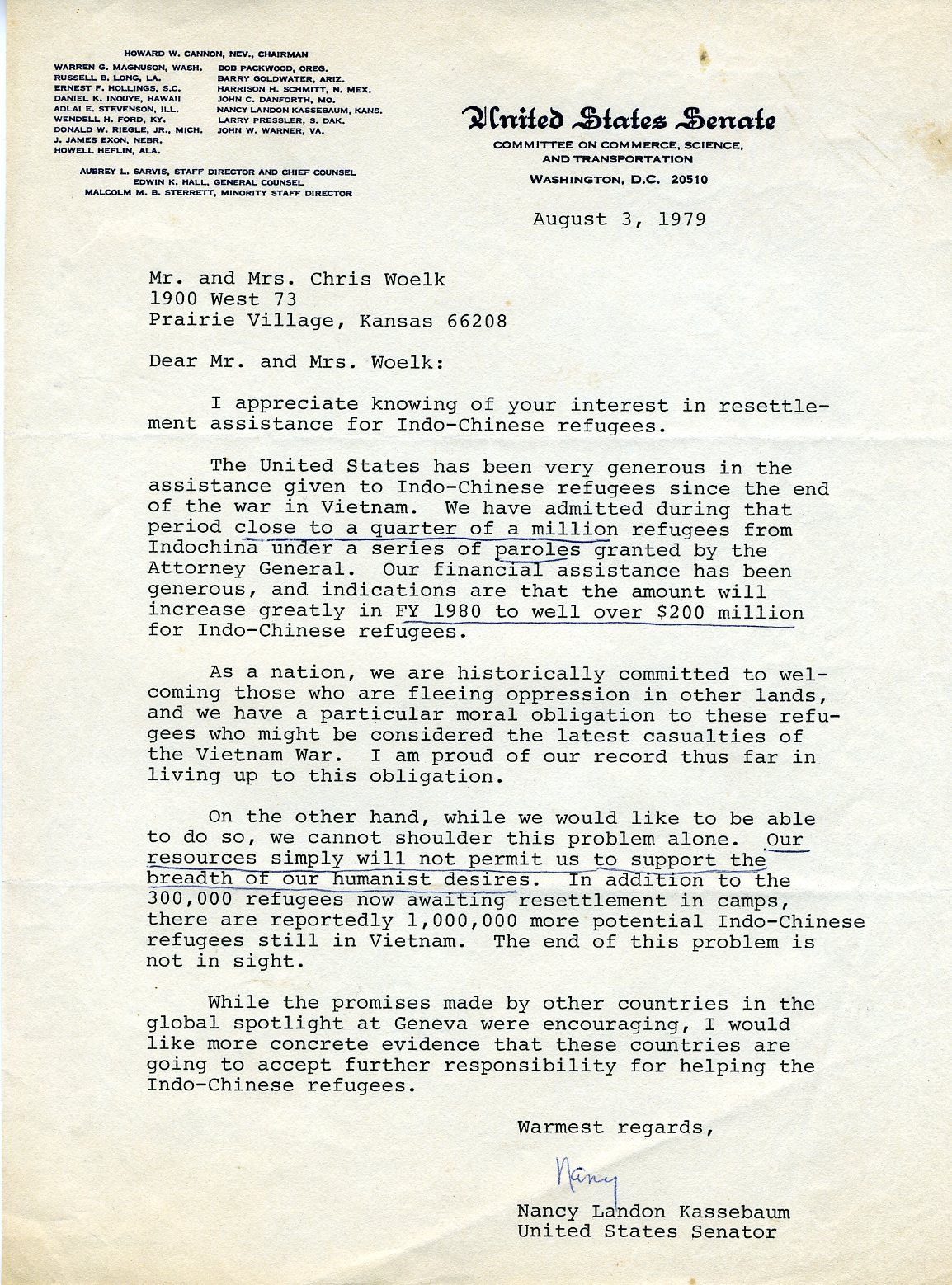

The following is a letter my wife, Candy, and I sent to Senator Kassebaum, along with her response on July 27, 1979. This was the time Vietnamese refugees, called the boat people, were becoming prominent in the news. We were pleading with the government to save them.