You may be wondering why an entire chapter on trash would be included. And, I will admit that had I not been in the Vietnam War, that would have been my first reaction as well. Trash – who cares, right? The answer to that is the impoverished Vietnamese families near our base for sure and those of us in the base, as the amount of trash at a firebase is monumental, constant and very often dangerous. It was part of our lives 24/7. And, it exemplifies some of what isn’t covered by the press and other media.

While important aspects of war are, and should be, covered, the daily struggles and life of the soldiers fighting it can get buried in the big news. But to those soldiers and their families, it’s not “news;” it’s their lives. Trash was an ever-present aspect of life in a firebase, and while we combated it with humor whenever possible, it was far from a laughing matter.

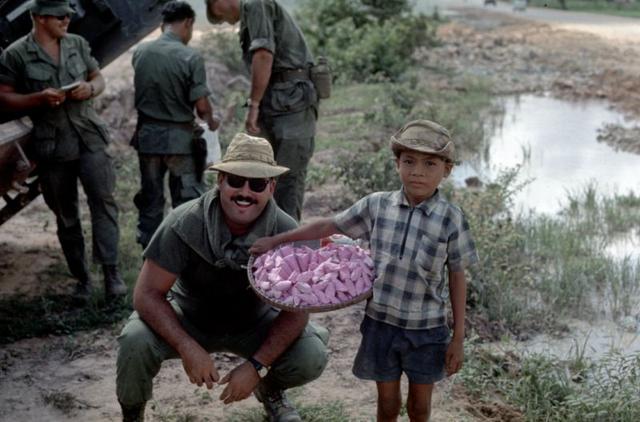

One thing I quickly realized during my time at the base was that trash was an American concept that the Vietnamese just did not have. I never saw any evidence of trash except ours, which the Vietnamese took as soon as possible. The material wealth disparity between low-wage soldiers and local Vietnamese was so large it defies easy description. Vietnamese farm families in the local community seldom had body fat and often appeared to be slowly starving. We were like multi-millionaires compared to them. What I made in a month was what a Vietnamese farmer made in a year.

So, base camp trash became part of their sustenance. It was a mixture of food waste from cooking, along with the food scraped from our mess hall plates, yet it was furiously fought over in a life and death struggle to be swallowed – on the spot and at exactly the time it was dumped into the massive hole which was the Tay Ninh base camp trash dump. Along with the food scraps, there was a mix of items that compose things Americans throw away. Paper, cardboard, wood and tin roofing, along with used or destroyed capital items and lots of miscellaneous “stuffs.” Circulating in and around the dump was such a massive swarm of flies it obscured the far edge of the 200-yard long pit. Flies covered everyone and everything. The food scraps that women and children were literally stuffing down were fly covered, as were the inside of their mouths. Even though the fly swarm was being slowly eaten, it wasn’t fast enough to have any impact on the increasing numbers.

- Donated American tin roofing. My photo

- Ammo box trash John Clark photo

Each truck leaving the dump was processed through a delousing station where every square inch on the surface was sprayed with insecticide, but when the truck left, it was still well decorated with flies hitching a ride and a swarm trying to get aboard as the vehicle sped away. Then, as the truck picked up speed, clouds of hitchhiking flies peeled off of the sides. Trucks were sprayed right after they left the dump, but against hordes, even of small creatures, there’s not a lot you can do.

Not only were the many women and children scavenging the dump and ingesting flies, they were in danger every moment. Several specialized large-tracked dozers moved about pushing items dumped at the edges of the pit towards the center and compacting as they went. The seemingly random movements of the machines and the keen competition to get to trash first made things perilous. Trash being dumped from the edges of the pit often landed on those trying to be first to the new inventory. It was a truly horrific and unnecessary scene. We could have given them the leftover food as part of the winning hearts and minds effort. But that wasn’t happening, as we were never to interact with the Vietnamese. The MPs letting them into the dump in the first place took a small risk. And it’s hard to say why they let them in – compassion or just didn’t care were both possible. I get why interacting was banned; we never knew if a Vietnamese was friend or enemy.

When I think of those who could have been fed off of our waste, it is just another reminder of the inhumanity, the impersonal nature war creates and often requires. As horrific as all of this was and as difficult as it was to accept, much less see, the dump provided some benefit to a people who were truly destitute. It was trash that made a difference – a statement I would have never made before Vietnam.

Trash that wasn’t food was sorted and closely examined, and I assume removed from the dump area, but I have no idea how, as the dump was guarded by our military police. Having visited the dump one time, which was one time too many, I can only guess that it was guarded and lit 24 hours per day because if it wasn’t, the dump would be empty by morning. Classifying sheets of tin roofing as trash may explain why most homes in Tay Ninh had graduated from roofs of plant matter to sheets of metal during my tour. Calling the tin roofs trash rather than aid may be unfair or calling its movement theft might be too strong. No matter, it was as common as the presence of leeches in Vietnamese homes and businesses. A positive legacy of our national involvement in Vietnam, even more so if it is still in use? I hope so!

- Very large roadside market Randy Barnes photo

I guess graft and corruption were mostly responsible for the tin distribution, but some may have come from “civil action” operations or pulled from the dump. However, I believe the bulk of it was sold or traded by someone who sold or traded with other local Vietnamese. Gossip was that the Philippine Civil Action Group based in Tay Ninh base camp was a major player in trading or selling a wide variety of American material in Vietnam or sending it home. This group was specifically there for hearts and minds so fought only when attacked or cornered. But, maybe because of opportunity or because “everyone else was doing it,” selling and trading illegally was rampart, even with those who might never have done so before.

Trash was very different at the firebase, as we ate canned or packaged food and what little was left was added to other trash that could be burned. A small hole, what we called a sump, was all that we needed, since we were basically camping. The main focus of our trash efforts at the firebase came from ammunition, as we shot, on average, 600 105mm artillery shells, every single day, every single week. As delivered to our base, a box of two shells weighed 107 pounds, which translated to 300 boxes in the trash every day. Each round was contained inside a fiber container and had a heavy cardboard protector covering the firing pin – more trash.

Many boxes were taken apart and put to good use or filled with dirt, so the box could be incorporated into protecting our bunkers from mortar or rocket attack, but many were burned. All metal parts were picked up after the fire cooled and shipped to base camp. This included the metal hinges, clasps and screws that secured them to the wood. After a 105mm round was fired, the brass casing remained and could not be burned, so that also needed to be transported to base camp. Adding to the fact that our FSBs were in off-road locations was a six-month wet season when some of the dirt roads were impassible. Moving trash was a major and time-consuming undertaking. Since few of the roads we traveled were other than dirt, our option was to use resupply helicopters that were not easy to find, much less be convinced to take a load of trash back to base camp. We were nothing if not creative in trying to reuse this never-ending trash, as we took a few of the fiber containers and buried one end, leaving the other to become the business end of a urination station. The “piss tubes,” as we so fondly called them, helped but not by much as most of the packaging and aftermath of 600 shells per day was trashed – again and again and again.

Food scraps, tin, artillery remnants – you’d think the trash issues would stop there. Not even close and that’s not counting human waste, which is a whole other story. The final trash element for this particular story was one that was extremely dangerous: the gunpowder that was not used to fire each of those 600 projectiles. The gunpowder was contained inside cloth bags that varied in size, and the bags were attached to a few long threads of string. Each bag was numbered one to seven, and a firing order from Fire Direction Control included the number of powder bags to be used, with the rest to be removed. During sustained shooting days, this trash seemed to fill the base and definitely slowed our movements. To destroy the powder without losing any part of our bodies in the process, one method was to empty the powder in a long, narrow line that wove around parts of the FSB, light one end and then watch the fire race to the far end. Any spark or flame could set the extremely volatile powder going, which made this method risky if it were to go off too soon. Another method was not just risky; it was dangerous. We would carefully transport it outside our base, along with out-of-date ammunition, and blow up a tree or something. Dangerous but fun to watch.