The rural Vietnamese did not sit on the ground as we Americans did. Starting from a standing position, they lowered their butts close to the ground, while keeping their feet flat on the ground and their torso leaning forward. It looked so different from an American sitting down that you couldn’t help but notice it, especially when it was a group. It was such a unique position that it was both eye-catching and, to us, unnatural.

No American I knew could get comfortable sitting this way but then few tried, unless goaded or a spontaneous challenge forced them into it. I tried squatting while filling sandbags with my FDC confidant, Vic Cooper, but that posture did not feel good or relaxing. I had to stand up just a few moments after attempting it, as I could not take the pain in my thighs. Instead, I stacked two or three sandbags to plop my butt on while holding bags as my partner shoveled in the sand – the American way.

In base camps, Vietnamese women were hired to fill sandbags with material piled up by Army Engineers. A circle of them could work eight hours in this position, laughing and spitting betel nut juice. The women worked at a slow, steady pace in contrast to us. We American studs got off to a roaring start but would begin to fade after a few hours. They worked slowly and steadily, while we would take breaks, get drinks and engage in other forms of relief. They kept at it the entire time, and the net result was that they out-produced us over seven or eight hours. The Mama Sans were glad to have the job and were paid the princely sum of five dollars per day, about what the Army was paying me for 24 hours. I did get free room and board, while these women did not. Plus, I was getting out of Vietnam after a year, and they were not.

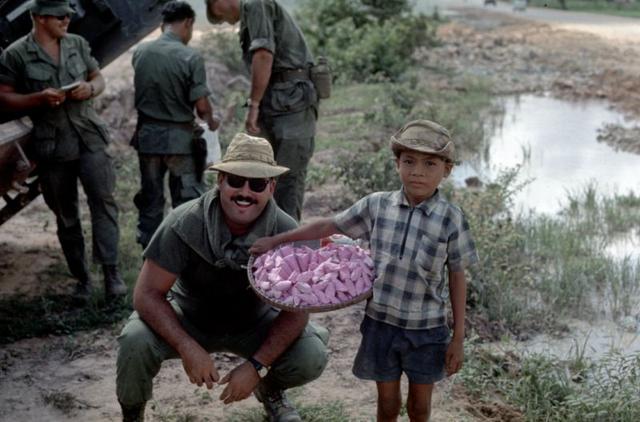

- Village market. Randy Barnes photo

- Lunch Randy Barnes photo

The way they squatted was a physical representation of one of many Vietnamese cultural norms that were “hidden” from us. This was a culture that had developed over millenniums, and even though local Vietnamese didn’t have the education and technology we did, they had a sophisticated and carefully followed social structure. There appeared to be unspoken social guidelines, a somewhat stylized way of acting around each other and even a certain nonabrasive tonality to their speech. Above all, I noticed an extreme and consistent level of courtesy and a significant amount of smiling and laughing. In miserable conditions, they were decidedly good-humored.

In addition, they were the hardest-working people I had ever seen, and I had seen some seriously hardworking farmers where I grew up in Russell, Kansas. The Vietnamese worked dawn to dusk, and I doubt they were thinking about democracy or communism or any of the other “isms” as they labored in full sun while standing in water. They were trying to live already difficult lives that had now been compounded by war. My guess is they would tell us not to let the door hit us on the way out if they could. Yet despite poverty and war, they still laughed, worked together and mostly treated each other with respect. All my thoughts about their culture derived from observation because I could not understand a word they said.

Something that couldn’t be missed when watching the women work was the fact that they chewed betel nuts the entire time. Teeth-blackening, gum-reddening betel nuts. It made their gums so red, it looked like they were about to start bleeding. Nonetheless, many chewed constantly.

Betel nut is the seed of a palm tree, which was chewed by many locals, mainly women. Women and children made up 90% or more of the visible rural civilian population. Most visible civilian males were below age 16, old men or those who were in the military service age group but obviously crippled. In the isolated area where I was stationed, it was basically a women and children society and other than the kids, many of them chewed.

GI folklore was that it contained a mild narcotic. It was said the Vietnamese used it to reduce hunger and fatigue. Humans have always found ways to alter their consciousness, especially during times of brutality and strife, so I assume that the betel nuts helped them get through their day. It was an accepted, possibly expected, part of rural culture.

Chewing betel nuts is not a pleasant experience, trust me. While waiting for a convoy from Dau Tieng to get moving, I tried to talk with the Vietnamese who were also waiting for it. An old woman (over 21 – people aged rapidly when living in rural Tay Ninh) with the telltale blood-red mouth and black teeth offered me a flat, hairy, green fruit or seed. I guessed she was telling me it was betel nut and that I should chew it. I hesitated, but then I took it, washed it off thoroughly with American canteen water, put it in my mouth and began to chew. After two or three chomps, it was too bitter to keep chewing, and I spit it out. The woman had a good laugh at my inability to handle it. I joined in her laughter because even though I had failed her test, I would not be walking around with the betel-nut look.